Failure is tricky, isn’t it? It is a bitter pill to swallow. But it is also the best route to growth.

As Jack Ma, the brains behind the Alibaba Group Holding perfectly puts it - “If you don’t give up, you still have a chance. Giving up is the greatest failure”.

Failure is tricky, isn’t it? It is a bitter pill to swallow. But it is also the best route to growth.

As Jack Ma, the brains behind the Alibaba Group Holding perfectly puts it - “If you don’t give up, you still have a chance. Giving up is the greatest failure”.

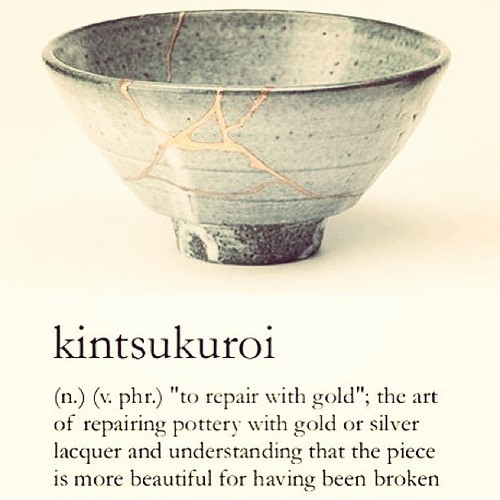

If we accept that throughout our career, we will have to embrace moments where we fail and use it to our advantage, perhaps our perception towards something so frowned upon can be changed. Organizations. Leaders. Managers. Peers. Parents. Everyone can play a part in that movement to turn failures into a learning process and yes like Kintsugi, it can even be beautiful. But what kind of failures are worth investing in? Do smart failures even exist? What then, does it mean, to fail and fall with grace?

Epic failures

It is almost impossible to talk about failure without mentioning the people who have been through the gut-wrenching pain of failing and came out on the other side, wise and successful:

Steve Jobs – Fired from his own company

Jack Ma – Isn’t good at math or programming even though his company is a tech company, and has gone through a series of rejections very early in his life, enough to crush anyone’s dreams

Elon Musk– Famously tried new business ventures and went into the verge of bankruptcy many times

What do they have in common? Overcoming moments where the future seems nothing but bleak.

But what’s stopping us from taking risks where we may fail?

Most job seekers feel they don’t trust that the low point(s) in their careers can be accepted by their potential hiring managers. Those who are working believe that failing to perform itself will cost them their job. Failure has become so distasteful, it is almost a reflex to think that it immediately translates to inadequacy and rejection.

Sometimes in high-stress situations, it is easy to magnify failures: mistakes such as human errors, an oversight in the processes, a misquoted deal, a failed innovation, an idea that overlooked a major component, a technical error, a placement or a sales procedure gone wrong are curveballs that can be accepted as potential areas of development.

The key is whether if you do a post mortem to learn from it well or are you making the same mistake over and over again. A lot of people refuse the post mortem process because it makes them feel inadequate so they choose to bury it and move on only to make the same mistake later.

At the end of the day, it is our ego, our perceived notion of how we should be viewed and the need to be accepted and approved by others. That versus how much we believe in our cause, our vision, that desired outcome from our actions. If we can reduce that need in the former, or have a burning intensity for the latter where you wake up every day knowing why you do what you do, failure becomes the process to success, instead of the end state. In fact, there are companies who take embracing failure seriously:

Some companies embrace failures so seriously, they adopt a performance review technique where employees are supposed to record their “bravest and best failures”. Advertising firm Wieden+Kennedy COO Neil Christie explains, “[We] encourage people to try things that sometimes they can’t do. If they’re never failing, then the suggestion is that they’re not trying hard enough”.

Unfortunately, it is not up to the employer to encourage a learning curve after a bad fall.

But you can take this step on your own.

Whether your company is big on embracing falls or not, you are constantly surrounded by the greatest examples of people who tried and failed and tried again. The list can go on with stars like Elvis Presley, Michael Jordon, J.K Rowling or even KFC’s Colonel Sanders.

Chances by the time you are in mid-career, you have probably made a couple of mistakes in your career.

Some are reversible, some are not – leaving permanent marks, just like the ceramic bowl here.

The lesson here isn’t that these people now sit on a boatload of money or fame and glory. The crux is that they never gave up even when almost everyone rejected them at their lowest points. Failing and falling is part of living. We have to learn to go through that with grace, with as much understanding and resilience we can muster. It is easier said than done, but the inner voice to want to do better should always holler louder than your biggest insecurity.

Like the Japanese art of Kintsugi, each “scar” is a learning journey, an experience, a part of our lives that made us who we are. Each of us should look for a way to cope with failures in a positive way, learn from negative experiences, take the best from them and convince ourselves that exactly these experiences make each person unique, precious.

Written by Josephine Chia and Yasmeen Banu